LIVELab Studies

What does musical group flow really feel like?

Being in “flow”—being pleasurably absorbed in a task that is challenging but manageable, to the point of losing track of time and self, often described as being “in the zone” where everything seems to “click”—has been studied extensively in individuals. But flow can also occur in groups, through coordination, mutual responsiveness, and shared awareness during a task. Music performance may create a special kind of group flow that relies on continuous mutual prediction to keep musicians’ actions aligned in time. To understand the experience of musical group flow, we first collected written descriptions of 85 musicians’ peak group musical experiences and identified the main themes using thematic analysis. The main themes were: group cohesion, collective effort, mutual enjoyment, fluid interaction, automaticity, holistic awareness, and altered state of consciousness. We then used these themes to create 71 survey items, which we gave to about 600 musicians. Exploratory factor analysis of their responses revealed a five-factor model that matched the themes from the qualitative analysis, providing empirical support for the idea that musical group flow is a unique group-level phenomenon that arises from smooth interpersonal coordination and creates a special mental state of mutual absorption, cohesion, and connection. This research helps explain why playing music with others—whether in professional groups or just with friends—can be so rewarding.

Being in “flow”—being pleasurably absorbed in a task that is challenging but manageable, to the point of losing track of time and self, often described as being “in the zone” where everything seems to “click”—has been studied extensively in individuals. But flow can also occur in groups, through coordination, mutual responsiveness, and shared awareness during a task. Music performance may create a special kind of group flow that relies on continuous mutual prediction to keep musicians’ actions aligned in time. To understand the experience of musical group flow, we first collected written descriptions of 85 musicians’ peak group musical experiences and identified the main themes using thematic analysis. The main themes were: group cohesion, collective effort, mutual enjoyment, fluid interaction, automaticity, holistic awareness, and altered state of consciousness. We then used these themes to create 71 survey items, which we gave to about 600 musicians. Exploratory factor analysis of their responses revealed a five-factor model that matched the themes from the qualitative analysis, providing empirical support for the idea that musical group flow is a unique group-level phenomenon that arises from smooth interpersonal coordination and creates a special mental state of mutual absorption, cohesion, and connection. This research helps explain why playing music with others—whether in professional groups or just with friends—can be so rewarding.

PhD student researcher: Luc Klein

Low bass drives audience movement

One factor that influences how we move to music is the amount of bass, or low-frequency sounds, in the music. In previous experiments, we have found that lower-pitched notes trigger quicker brain responses and enhance movement timing. However, we had not yet tested whether bass directly causes increased movement—that is, if adding more bass at a concert actually makes people dance more. In a unique concert experiment at the LIVELab, we altered the music to include extra-low bass while measuring audience movement. During a performance by the renowned electronic music duo Orphx, we used special very-low frequency (VLF) speakers to add subtle VLF sounds to the music. We turned the VLF speakers on and off every 2.5 minutes and used motion capture to track how the audience moved. Even though the added low bass was so quiet that it could not be consciously detected, audience members moved more when it was present. We are now following up on this result to understand the physiological mechanisms that might explain why bass increases movement.

One factor that influences how we move to music is the amount of bass, or low-frequency sounds, in the music. In previous experiments, we have found that lower-pitched notes trigger quicker brain responses and enhance movement timing. However, we had not yet tested whether bass directly causes increased movement—that is, if adding more bass at a concert actually makes people dance more. In a unique concert experiment at the LIVELab, we altered the music to include extra-low bass while measuring audience movement. During a performance by the renowned electronic music duo Orphx, we used special very-low frequency (VLF) speakers to add subtle VLF sounds to the music. We turned the VLF speakers on and off every 2.5 minutes and used motion capture to track how the audience moved. Even though the added low bass was so quiet that it could not be consciously detected, audience members moved more when it was present. We are now following up on this result to understand the physiological mechanisms that might explain why bass increases movement.

Postdoc research: Daniel Cameron

Cameron, D. J., Dotov, D., Flaten, E., Bosnyak, D., Hove, M. J., & Trainor, L. J. (2022). Undetectable very-low frequency sound increases dancing at a live concert. Current Biology, 32(21), R1222–R1223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.09.035

Dance with many, dance with one: Optimizing learning to dance

Improvised partner dancing is a joyful activity that allows people to meet new friends, exercise, improve memory and coordination, and build self-confidence. In this activity, two people improvise and coordinate dance steps together. To do this, it is necessary to learn how to give and receive cues through physical contact, such as holding hands or an arm-to-shoulder embrace. This learning mostly happens through practice and trial and error. In group dance lessons, people can either switch partners during learning or keep the same partner. We wondered which approach is more effective for learning the non-verbal communication needed for coordination. We invited participants to learn a simple partnered dance exercise at the LIVELab. Untrained participants were paired with trained dancers to perform the exercise as synchronously as possible while holding hands. One group switched partners often, while the other always danced with the same person. At the end of the experiment, we measured how synchronized the couples in each group were to see which strategy produced better dancers. To measure synchronization, we recorded the dancers’ movements using motion capture, which allows us to measure the position of different body parts (e.g., head, shoulders, elbows, and feet) with high accuracy. Our results show that people who danced repeatedly with the same partner learned to synchronize better, even when tested with partners they had never danced with before. This suggests that, at least in the early stages of learning to dance with a partner, sticking with the same person may be more effective. Further studies are needed to see if this advantage continues at more advanced stages of training, when flexibility might become more important.

Improvised partner dancing is a joyful activity that allows people to meet new friends, exercise, improve memory and coordination, and build self-confidence. In this activity, two people improvise and coordinate dance steps together. To do this, it is necessary to learn how to give and receive cues through physical contact, such as holding hands or an arm-to-shoulder embrace. This learning mostly happens through practice and trial and error. In group dance lessons, people can either switch partners during learning or keep the same partner. We wondered which approach is more effective for learning the non-verbal communication needed for coordination. We invited participants to learn a simple partnered dance exercise at the LIVELab. Untrained participants were paired with trained dancers to perform the exercise as synchronously as possible while holding hands. One group switched partners often, while the other always danced with the same person. At the end of the experiment, we measured how synchronized the couples in each group were to see which strategy produced better dancers. To measure synchronization, we recorded the dancers’ movements using motion capture, which allows us to measure the position of different body parts (e.g., head, shoulders, elbows, and feet) with high accuracy. Our results show that people who danced repeatedly with the same partner learned to synchronize better, even when tested with partners they had never danced with before. This suggests that, at least in the early stages of learning to dance with a partner, sticking with the same person may be more effective. Further studies are needed to see if this advantage continues at more advanced stages of training, when flexibility might become more important.

How do different people experience live classical music?

Listening to music is a favorite activity for mood regulation, relaxation, and enjoyment. With the rise of personal music devices, music listening can now be experienced alone. Yet, people still love live concerts and rate them among their most memorable experiences. To understand why, we measured 20 audience members’ brain, heart, and skin responses at the most expressive moments during a concert where two pianists from the Canadian Chopin Society performed in the LIVELab. After each piece, audience members also rated their enjoyment, emotional intensity, familiarity, and feelings of connection with the audience and the performer. Performers provided annotations of the most expressive sections of their performance. We also collected continuous ratings of valence (positive/negative emotion) and arousal (intensity) from a new group of participants who listened to the pieces online. Interestingly, the results so far are mixed—with different people showing different biological responses to the music at different times. We are now interested in what factors might influence how a person experiences classical music.

Postdoc research leader: Martin Miguel

How do musicians learn to synchronize during expressive performances?

When playing expressive music that can speed up and slow down, how do musicians stay together? If they wait to hear what another musician does, it will be too late to stay in sync, so we investigated whether one musicians can predict what another musician will play next based on what they have just played. We asked several professional violinists to play along with a very expressive recording of "Danny Boy" several times in a row while we recorded their playing. We then used a mathematical technique called Granger causality to determine how much the recording influenced the violinists’ upcoming playing. We found that, at each moment during the piece, our violinists were influenced by how the recording had just sounded. Furthermore, as they played with the recording multiple times, the violinists became more and more synchronized with it, and relied less on predicting from what they had just heard. In other words, they built an “internal model” or detailed memory of the musical intentions of the violinist on the recording, which helped them coordinate ([So learning to play music with others is an amazing, complicated process involving prediction and building internal memories]).

When playing expressive music that can speed up and slow down, how do musicians stay together? If they wait to hear what another musician does, it will be too late to stay in sync, so we investigated whether one musicians can predict what another musician will play next based on what they have just played. We asked several professional violinists to play along with a very expressive recording of "Danny Boy" several times in a row while we recorded their playing. We then used a mathematical technique called Granger causality to determine how much the recording influenced the violinists’ upcoming playing. We found that, at each moment during the piece, our violinists were influenced by how the recording had just sounded. Furthermore, as they played with the recording multiple times, the violinists became more and more synchronized with it, and relied less on predicting from what they had just heard. In other words, they built an “internal model” or detailed memory of the musical intentions of the violinist on the recording, which helped them coordinate ([So learning to play music with others is an amazing, complicated process involving prediction and building internal memories]).

PhD student investigator: Luc Klein

Klein, L., Wood, E., Bosnyak, D., & Trainor, L.J. (2022). Follow the sound of my violin: Granger causality reflects information flow in sound. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 16, 982177. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2022.982177

Making music together: Incredible coordination!

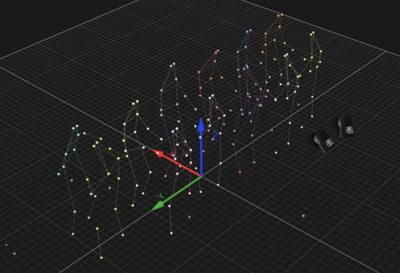

In order to play a musical instrument, the musician’s brain needs to anticipate what wants to play next in order to have time to plan and execute the motor movements to play the next notes. When that musician plays in, for example, a string quartet or a jazz trio with other musicians, there is an added challenge. The musician also has to coordinate with the other musicians – keep in sync, phrase together, and match each other’s musical styles. If each musician waits to hear what each other are doing, it will be too late to be with together with each other! So musicians not only have to anticipate how they are going to play next, they also have to anticipate or predict how their fellow musicians are going to play next. We have been studying how they do this. In one study, we used motion capture equipment in the LIVELab to measure the body sway of each musician. Just like how people gesture with their hands when they talk, and this helps them to speak fluently, musicians sway their bodies when they play music, and we think this helps them to plan the “big picture” of how they want to play the music. We showed, using a mathematical technique called Granger Causality, that from the body movements of one musician at one point in time, we could predict how another musician playing with them was going to move at the next point in time. In other words, through their body sway we could measure communication between the musicians! We found that musicians assigned as “leaders” influenced other musicians in the group more than those assigned as “followers”. In a second study, we found that the higher the communication among all the musicians, as measured by body sway coupling, the listeners rated the quality of the performance. So good communication through body sway leads to great music! We believe that these coordination dynamics that we are uncovering between musicians also apply to many other situations in which people need to coordinate their actions.

Chang, A, Kragness, H, Livingstone, S, Bosnyak, D, and Trainor, L (2019). Body sway reflects joint emotional expression in music ensemble performance. Scientific Reports, 9(205) View Abstract Full text PDF

Baby Opera!

We all know there's something special about a live concert, especially now when we can’t go to live concerts! Whether it's a famous singer or a guitarist at your favourite local restaurant, seeing a musician performing right in front of us enhances our experience of the music compared to hearing it on a recording. In this study, researchers from the University of Toronto Scarborough (and former PHD graduates from our Auditory Development Lab, Drs. Laura Cirelli and Haley Kragness) teamed up again with us to learn how babies experience an audiovisual recording of a concert compared to the real thing. Groups of 25-30 babies came to McMaster’s unique LIVELab research-concert hall (https://livelab.mcmaster.ca/) to watch a new musical show called "The Music Box" composed by Toronto artist Bryna Berezowska, either live or projected to the big screen. We recorded the babies’ reactions, as well as their physiological responses, like heart rate. It made for quite a lively event, and some of it was captured on this CHCH news clip feature (https://www.chch.com/mcmaster-university-teams-up-with-musicians-to-create-opera-for-babies/) The results of the study will help us better understand the role of live performance in our emotional and physiological reactions to music.

Kragness, H. E., Eitel, M. J., Anantharajan, F., Gaudette-Leblanc, A., Berezowska, B., & Cirelli, L. K. (2023). An itsy bitsy audience: Live performance facilitates infants’ attention and heart rate synchronization. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. Advance online publication.[Journal]

Analyzing attraction in speed dating: Turning the LIVELab into the LOVELab!

Social bonding is fundamental to human society, and romantic interest involves an important type of bonding. The role of nonverbal interaction has been little studied in initial romantic interest, despite being commonly viewed as a crucial factor. Speed dating is an excellent situation for investigating initial romantic interest in real-world settings, as involves a common real-world activity while at the same time allowing us to have high experimental control. We conducted a real speed dating event in the LIVELab while we measured the body sway of the participants using motion capture. The results showed that people’s long-term romantic interest can be predicted by nonverbal interactive body sway communication, above and beyond their ratings of physical attractiveness. In addition, we found that the presence of groovy background music during speed dates promoted interest in meeting a dating partner again. This novel approach to measuring non-verbal communication could potentially be applied to investigate nonverbal aspects of social bonding in other dynamic interpersonal interactions such as between infants and parents and in nonverbal populations including those with verbal communication disorders.

Chang, A, Kragness, HE, Tsou, W, Bosnyak, DJ, Thiede, A, and Trainor, LJ (2021). Body sway predicts romantic interest in speed dating. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 16(1-2), 185-192 View Abstract Information/Download

https://www.chch.com/speed-dating-study/